The video discusses NVIDIA’s new AI system, ADD, which uses an AI judge to automatically evaluate and improve digital character movements, overcoming the manual tuning limitations of previous methods like DeepMimic. This approach produces highly realistic, fluid, and adaptable animations across various complex motions, marking a significant advancement in digital character animation.

The video explores the challenge of making digital characters move exactly like humans. While motion capture technology can record human movements such as running, jumping, or reading papers, simply copying this data into a computer program is not enough. Virtual characters have muscles and joints that require calculating the forces and torques at every moment to mimic realistic motion, which is a complex and difficult task. A breakthrough came in 2018 with the DeepMimic paper, which turned motion imitation into a game where every joint and movement had a score. The system learned to imitate motions by maximizing this score through trial and error, producing impressive and lifelike animations.

However, DeepMimic had a major limitation: all the scoring criteria had to be manually designed and fine-tuned. Researchers had to decide how much to reward or punish specific joint angles, balance, and foot placement, which was time-consuming and fragile. Changing the motion or the character’s body required re-tuning these parameters, making the system cumbersome and reliant on expert intervention. This manual tuning was described humorously as being held together by “duct tape and the tears of PhD students,” highlighting the need for a better, more automated approach.

The new paper introduced in the video, called ADD (Adversarial Differential Discriminator), replaces the hand-crafted scoring system with an AI judge that learns automatically what a perfect performance looks like. Instead of juggling multiple scores for different body parts, the AI judge provides a single verdict on how close the motion is to real human movement. As training progresses, the judge focuses on parts of the motion that still look unnatural and pushes the character to improve them. This approach automates the evaluation process and reduces the need for manual tuning, making it more adaptable and efficient.

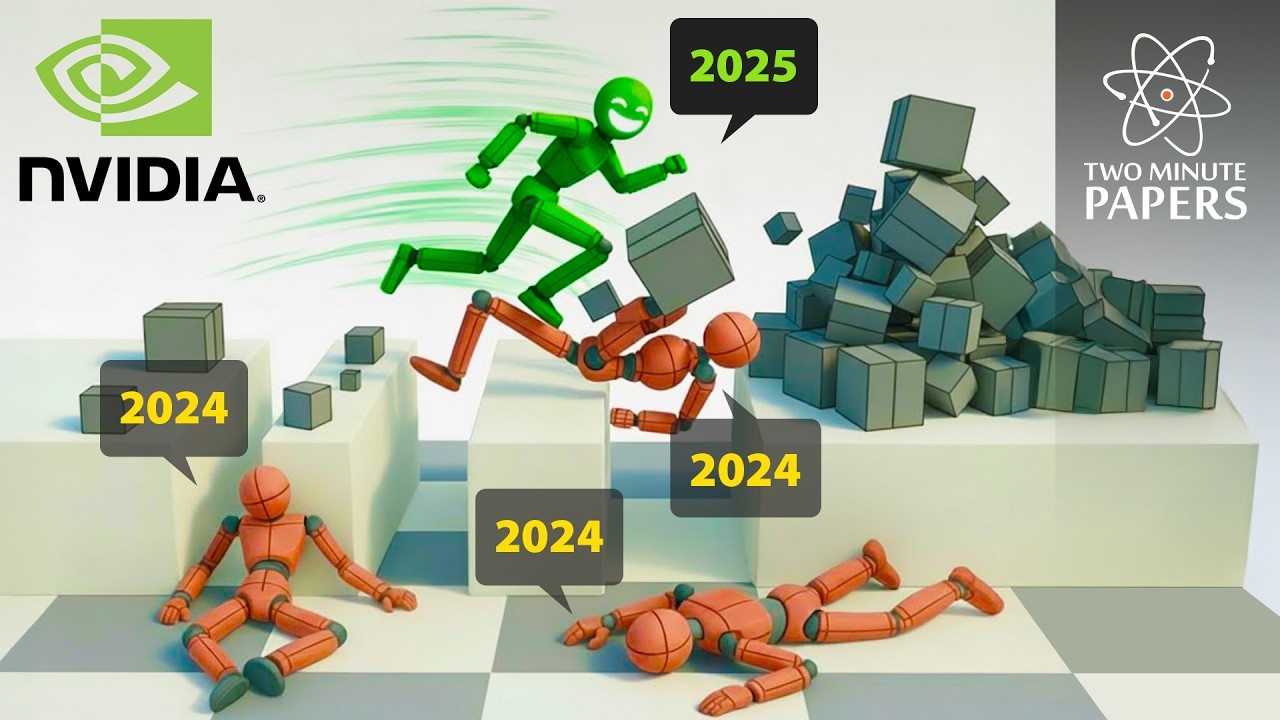

In tests, ADD performs as well as or better than DeepMimic, especially in challenging movements like parkour, climbing, and jumping. The motions generated by ADD are fluid, believable, and physically accurate, controlling all joints correctly. It also retains the versatility of DeepMimic by working on different body morphologies and behaviors, including robot control, falling and getting up, and various activities like karate or walking an invisible dog. An ablation study in the paper confirms that each component of the system is necessary for its success, demonstrating the robustness of the approach.

Despite its impressive results, ADD is not flawless. The AI judge sometimes struggles with flashier tricks, occasionally giving up mid-performance, similar to a dance judge confused by unexpected moves. Nonetheless, this research marks a significant step forward in digital character animation, showing that AI systems are beginning to understand human motion deeply. The video emphasizes the importance of sharing and discussing such research to advance the field and looks forward to even more realistic digital creatures in the near future.